(1776-1837) was one of the pioneers of plein-air oil painting in England. He became convinced around 1802 that he should paint in oil outdoors, believing that Claude Lorrain had done so, even though Claude actually used only water-based media or drawing tools in his outdoor work.

Paint Boxes

Here is one of Constable's surviving oil sketch boxes. The glass vials were a way to carry medium and pigment, as tubed paint didn't come along until 1841. Another way to carry mixed paint was the urine bladders from pigs or other animals, something you could pick up from a butcher.

|

| One of Constable's wooden sketching boxes, 9.25 x 12 inches. |

According to an

exhibition catalog of his oil sketches, this paint box "shows the removable panel that fits into the lid, creating a separate compartment, that Constable used for carrying small pieces of paper, canvas and board. Wet sketches were piled in here on the homeward journey. The panel could also be used as an impromptu palette or as a flat surface for standing bottles of oil, turpentine, and other materials during painting."

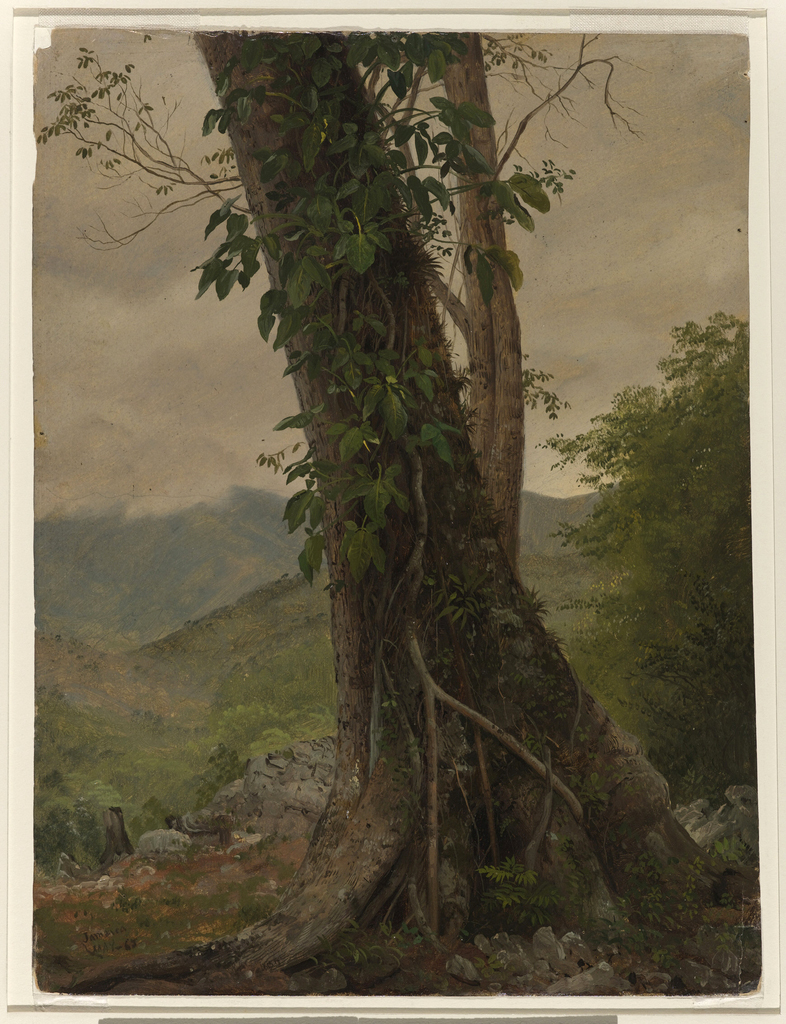

I don't know if I would agree with the authors that wet sketches were "piled in" to such a box. My guess is that Constable would have used a box like this open in his lap with the lid away from him as he sat on a tripod stool. The sketch would be pinned into the open lid, and kept pinned there until it was dry enough to handle. This was how Americans, such as Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, and William Trost Richards did it.

Here's another paint box, divided into "seventeen compartments and contains a cork-stopped glass phial with blue pigment, a lump of white gypsum probably used for a variety of purposes including drawing and roughening paper, and various bladders with the artist’s own or commercial ready-mixed paint." Try getting this one through the TSA.

|

| Constable plein-air study showing red-brown colored ground |

Surfaces

Constable's studies were usually painted on heavy paper or millboard. Millboard was made from a mixture of cotton, flax, wood, and other fibrous material. The priming was a "viscous medium-rich oil ground containing a small amount of red and black pigment."

(Source)

The priming, prepared in batches in advance of his painting sessions, saturated and sealed the sheets. I couldn't tell from my research whether he sized his surfaces before applying the oil ground. Later painters typically sized (or sealed) the paper or board with shellac or rabbit skin glue. By the 1820s, Constable was using commercially-prepared millboard or "Academy board," which was specially made for artists.

(With modern materials, I would use

acrylic matte medium

to size the paper or board before applying an

oil ground

. You can use the matte medium over brown- or gray-toned paper to keep that natural paper color, or make up your own toned oil-based ground over the sizing. Allow time for it to dry thoroughly.)

Color Palette

One of his surviving plein-air palettes was analyzed for paint ingredients, including vermilion, emerald green, chrome yellow, cobalt blue, lead white and madder, ground in a variety of mediums such as linseed oil mixed with pine resin.

|

| Constable sunset study, probably painted all in one session (or alla prima) |

Working Method

At times it can be hard to tell whether a given sketch was done entirely on location or whether he touched them up after returning to the studio. Chemical sleuths have found that some sketches contain slow-drying mediums, such as poppy oil, which would have allowed him to rework his surfaces over extended periods of time, but that doesn't prove anything. To my eye, based on the efficiency and urgency of the paint handling, the ones shown in this post look to be done entirely on location.

Written Notes

Constable often jotted notes on the back of his paper or boards. For example: "Very lovely evening—looking Eastward—cliffs (and) light off a dark grey sky –effect-background-very white and golden light."

Sources and further reading

Books:

Constable's Oil Sketches 1809-29

, edited by Hermine Chivian-Cobb, Salander-O'Reilly Galleries, New York, 2007

The Painted Sketch: American Impressions From Nature, 1830-1880

. Well researched exhibition catalog which focuses on American plein-air practices.

Websites:

Constable Sketches Up Close and Personal (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Constable's Techniques (Tate Museum, London)

Lines and Colors Blog "

Constable's Oil Sketches"

Constable paintings at the

Yale Center for British Art

_cropped.jpg)